On a Tripod Worth More Than a Camera

Photoworks Journal #26

Here’s what a Kiev 88 camera looks like: a rotund black box, square, not tall, like a portable projector. The edges are lined with reflective metal. You navigate the shutter button on the right, and you remove the metal slide on the left to expose the film to light. On the hot shoe, the Kiev 88 logo is engraved, the only branding. The camera was made in the Arsenal Factory of the Soviet Union (and, later, Ukraine), which previously housed camera parts made by the German company Zeiss. During the Nazi Party’s reign, Zeiss became a subcamp filled with forced labourers, but during World War 2, the Soviet Union siezed the factory, along with its products. Later, Arsenal manufactured its own cameras that were more affordable and egalitarian than the ones made by Zeiss. The Kiev 88, which was first released in the mid-1980s, became the most popular.

In shape and form, the Kiev 88 bears an eerie resemblance to Zeiss’s Hasselblad 1600F, which was released in 1948, nearly four decades earlier. The Kiev 88 was nearly three times cheaper than the Hasselblad, however, and, in many ways, Arsenal was acutely aware of what this new camera was conveying. Often mockingly called the Hasselbladski, the general vibe is that the Kiev 88 is a counterfeit Hasselblad 1600F, an illegitimate half-brother. On YouTube, vintage camera vloggers often speak of it in dismissive, caustic tones: ‘The Kiev 88 is a very cheap way to get into medium format cameras,’ one review begins. ‘It’s on a tripod worth more than the camera,’ another states. Comments about its relative ‘cheapness’ (a quality that is wholly reliant on the assumption that your audience shares your definition of ‘cheap’) also serve to reify the Hasselblad as a metonym for photographic sophistication in contemporary Western culture, positioning the Kiev 88 as a Soviet-era troublemaker against the venerable Hasselblad, the first camera on the moon and the camera du jour of oligarch family portraits.

Even on message boards, users warn others of the technical quirks of the Kiev 88 while valorising the toolbelt of screwdrivers needed whenever the Hasselblad’s shutter jams. However, despite the detractors, many people take joy in owning and using the Kiev 88. On Flickr, the neglected photo-sharing platform, misty landscape shots and sunset drenched portraits clearly demonstrate the dexterity of the camera’s light sensitivity and functionality. Yet claims that the Kiev 88 is counterfeit linger, a reputation that is proving difficult to shake.

Whenever an industry blooms, so too do counterfeits and cheap alternatives. They’re the long shadow behind consumerism, and fake goods abhor a vacuum. In the makeup and skincare industries, so-called ‘dupes’ proliferate as fast as the originals. Entire blogs are dedicated to finding inexpensive dupes that are made with the same ingredients as designer products but cost a fraction of the price. In the world of consumer electronics, Nokla and Damsung phones sit right next to their proprietary almost-namesakes in city markets across the Global South, such as the Toi Market in Nairobi. In fashion, many mock products branded as Caiwen Kelai or Cuggi, yet, as many of the producers of fake designer brands would tell you, their designs often include improvements and upgrades of the originals. In her essay ‘A Copy of a Copy’, writer Alice Hines sat with a producer of such garments, who noted how her version of an Alexander Wang sweater got rid of the scratchy wool design by adding more cotton to the fabric. In some rare cases, after countless legal battles, brands have even welcomed these intruders and imitators into their design houses: Dapper Dan now helms his own line with Gucci, the very brand whose prints he brazenly remixed in his 1980s designs.

With counterfeit cameras, however, there can be a mix bag of improvements and technical quirks: Mexican photographer Isai Carreto used the DL-9002V, a fake Canon, to shoot a model in various locations in Mexico. The images, sometimes dazzling and sometimes velveteen, have a peculiar, almost-haptic, three-dimensional feel. They make for an inviting contrast to the often flat and alienating mood of photographs shot on traditional DSLR cameras. The pulse of fake cameras is flexible and not fixed to a beat: sometimes double exposure occurs when the winding crank doesn’t complete a turn (a problem also faced regularly by Kiev 88 users.) One of his images, in which the smiling model’s face is juxtaposed with a city street, seems double exposed. It could be a glass reflection, but it’s hard to say in the zany world of fake cameras.

The lure of counterfeit cameras is less about the social cachet of appearing to own a luxury prop, and more about the fact that the memories and visual outlooks they capture are every bit as legitimate as those recorded with the real thing. This too can be said of ‘cheap’ cameras, often found at the ends of Ebay and pharmacy shelves. Cheap cameras can sometimes feel like the white-market equivalent of counterfeit cameras: both derided in photography communities with soured reputations for their unbalanced usability. However, the quirky-but-functional tag usually assigned to cheap cameras can often be a benefit. Such is the case for Sandy Kim, who has garnered a large following for her diaristic and DIY approach. Her photographs feel like voyeuristic treks through the bodegas, alleyways, and cramped apartments of New York and LA. Her subjects include the likes of musicians Sky Ferreira, Girls, and Young Thug, and she has shot covers for publications such as The Fader, Wonderland, and Purple. Most often, she ignores compositional arrangements. The grain of her images can be rough. When she takes self-portraits, shadows can sometimes take up much of the shot – it’s as if the quirks come first.

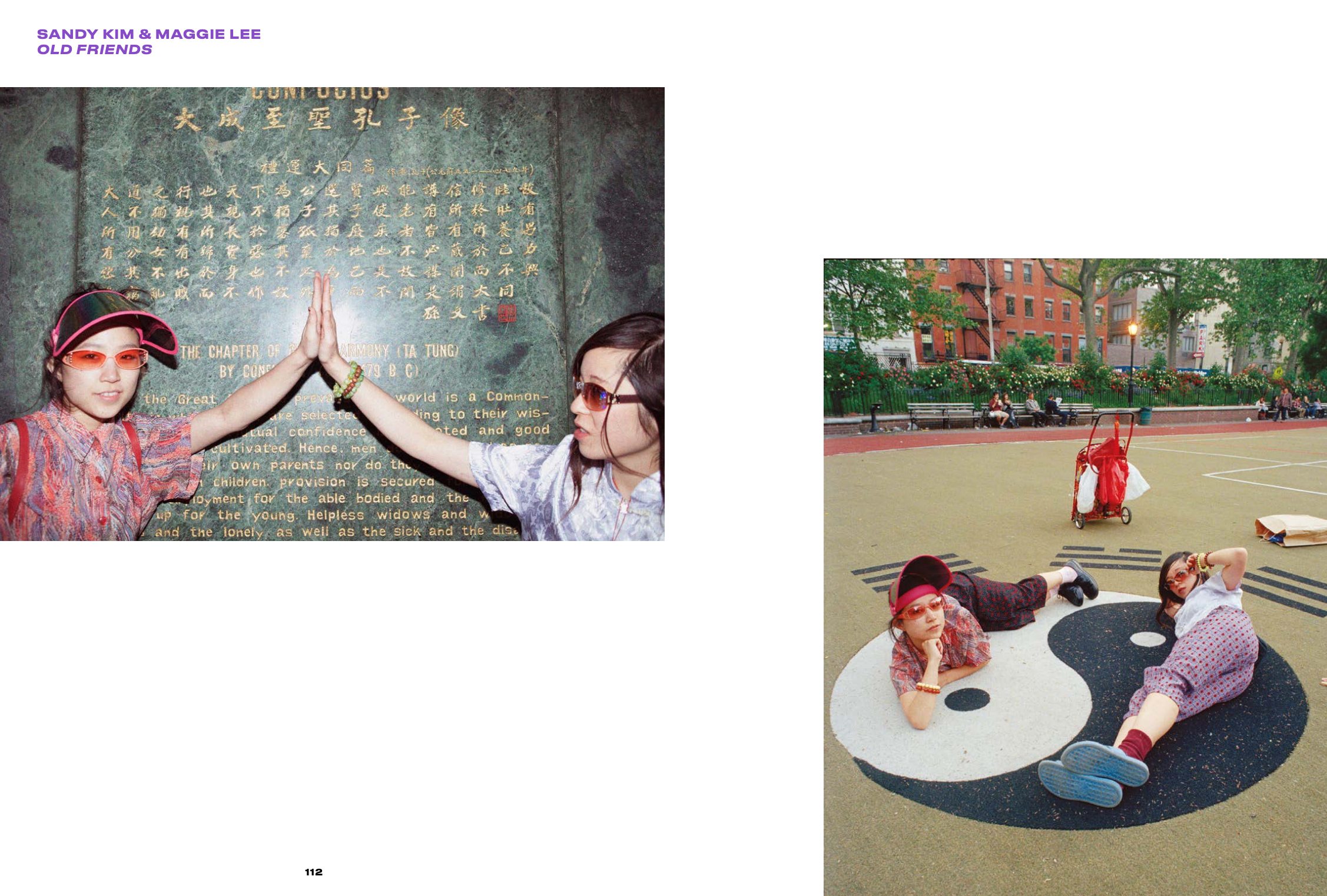

One of Kim’s most interesting projects is Old Friends, a collaboration with photographer Maggie Lee. The two stalk Chinatown in New York hunting for content, masquerading as elderly New Yorkers enjoying what the city has to offer. They clink their drinks in a busy restaurant, and lie on the ground, snake-like, posing as Yin and Yang. They high-five in front of a slab of stone engraved with texts by Confucius that read ‘Mutual confidence is promoted and good neighborliness cultivated … There is no need for people to shut their outer doors.’ It’s a playful and touching series, where ageing is anticipated, rather than dreaded. It also feels ephemeral – like the images might disappear if you glance away. This kind of image making seems like it would be nearly impossible if user-friendly, cheap, and disposable cameras weren’t on the market.

Cheap cameras, and the relationship we’ve come to have with them, are transient in mood as well as in the literal disposability of the cameras. They’re sometimes built and utilised as a cheap commodity and one that can be carried around for any occasion before ending up in graveyards in developer’s labs or living room drawers with other aged gadgets. Their energy and what they provoke (a relaxed instantaneity and freedom) continue to be sought after. As a branding exercise in 1998, Fujifilm, the legacy camera manufacturer, honed in on a nascent nostalgia for cheap and vintage cameras by introducing the Instax family of cameras as a modernised simulacrum of Polaroid instant film cameras from the 1970s. The current versions of the Instax are soft coloured, pebble looking objects. When a picture is taken, the exposed film rises from the top of the camera, arriving with the white borders of polaroids that convey a sort of digital/analog hybrid.

In Japan, where Fuji is located, polaroids are called cheki (チェキ) and they are a commonplace role in contemporary culture. Some restaurants offer to take cheki of you and your party before your meal. Cheki of J-pop idols are sold in convenient stores for roughly £5 and sometimes wedding guest books are replaced with cheki photo albums. Photographer Hideki Tonomura named her photobook Cheki, in which a model galivants for the camera in the dead of the night across tight hallways and spare playgrounds. When she’s static, the camera loses focus and the model becomes more explicit and eroitc. Tonomura’s work is often concerned with female sexuality, traced by portraits of women whose sense of autonomy can feel fuzzy, like her mother counting money, and herself as a former nightclub hostess. In Cheki, the white bordered images have an uncensored charisma, where the instance of being self-critical has no place.

Tonomura and Kim’s work points to a shift in how we view point-and-click cameras. If a photographer known for developing a style with low-cost equipment can shoot Sky Ferreira for the cover of Playboy or publish a photobook, who else can legacy publications open their doors to, and how far can this reach go before touching counterfeit camera users? Counterfeit cameras like the ones used by Isai Carreto have a long way to go before they’re embraced fully. They’re still flagged at the base camp of tolerance. Even though the fashion world shows that a different future is possible, it also suggests that this future is by no means guaranteed: Dapper Dan is still recovering from the effects of litigation that ran him out of business in the 90s, and in Shenzhen, counterfeiting factories are often raided. Suggesting that counterfeit goods open up inventiveness and egalitarianism in these industries is a hard sell to authorities, but the way in which consumers online emphatically embrace dupes and fakes could mean that at least the culture around them is changing.